The Fen Basin

Although not known for mountainous scenery or valuable outcrops of rocks such as marble and granite, the landscapes of the Fens do, nevertheless, have a fascinating earth history that makes this area of the country unique and of great value for geological and geomorphological study. For example, the fenland basin is underlain mostly by Jurassic clays that are world famous for the fossils of huge marine reptiles – as seen in museums such as Peterborough and the Sedgwick in Cambridge. Also of Jurassic age are the limestones that underlie Peterborough and other parts of the western and northern fen edge, known for their use as very important building stones, particularly for religious buildings such as the cathedrals of Ely and Peterborough, and many significant buildings in the fen edge city of Cambridge. A unique Jurassic ‘coral reef’ can be found on the edge of the Fens near Upware, by the River Cam, and Ely Cathedral itself lies on a high ridge of hard sandstone (Cretaceous ‘Greensand’) lifting it above the surrounding fenland and resulting in the iconic views from all around. Underlying the southeast edge of the Fens is the Cretaceous Chalk, again a famous rock, that forms some of the familiar downland landscapes of the country, and here, along with the limestones to the north, influences much of the ecology of the Fens due to the calcareous water it supplies.

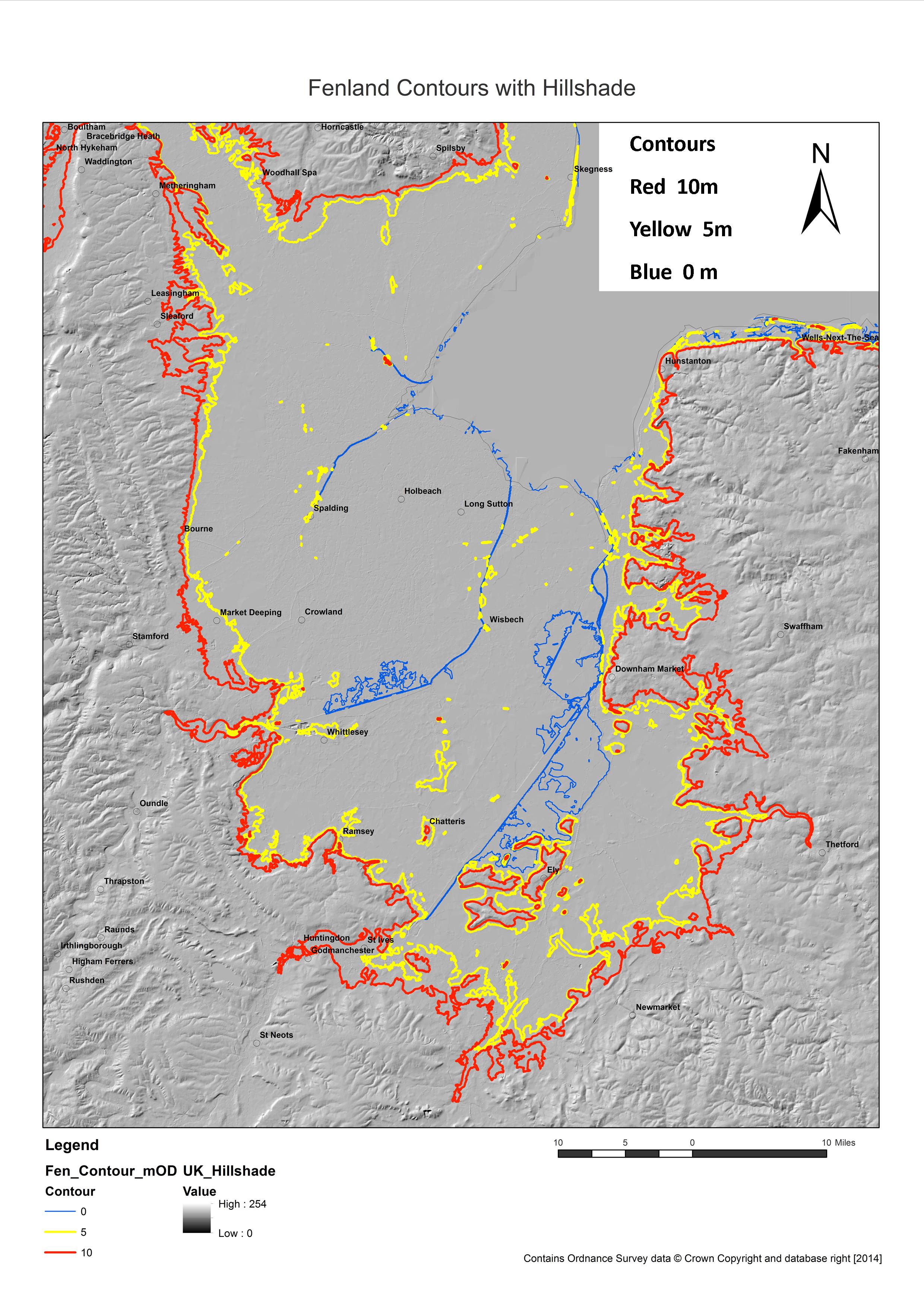

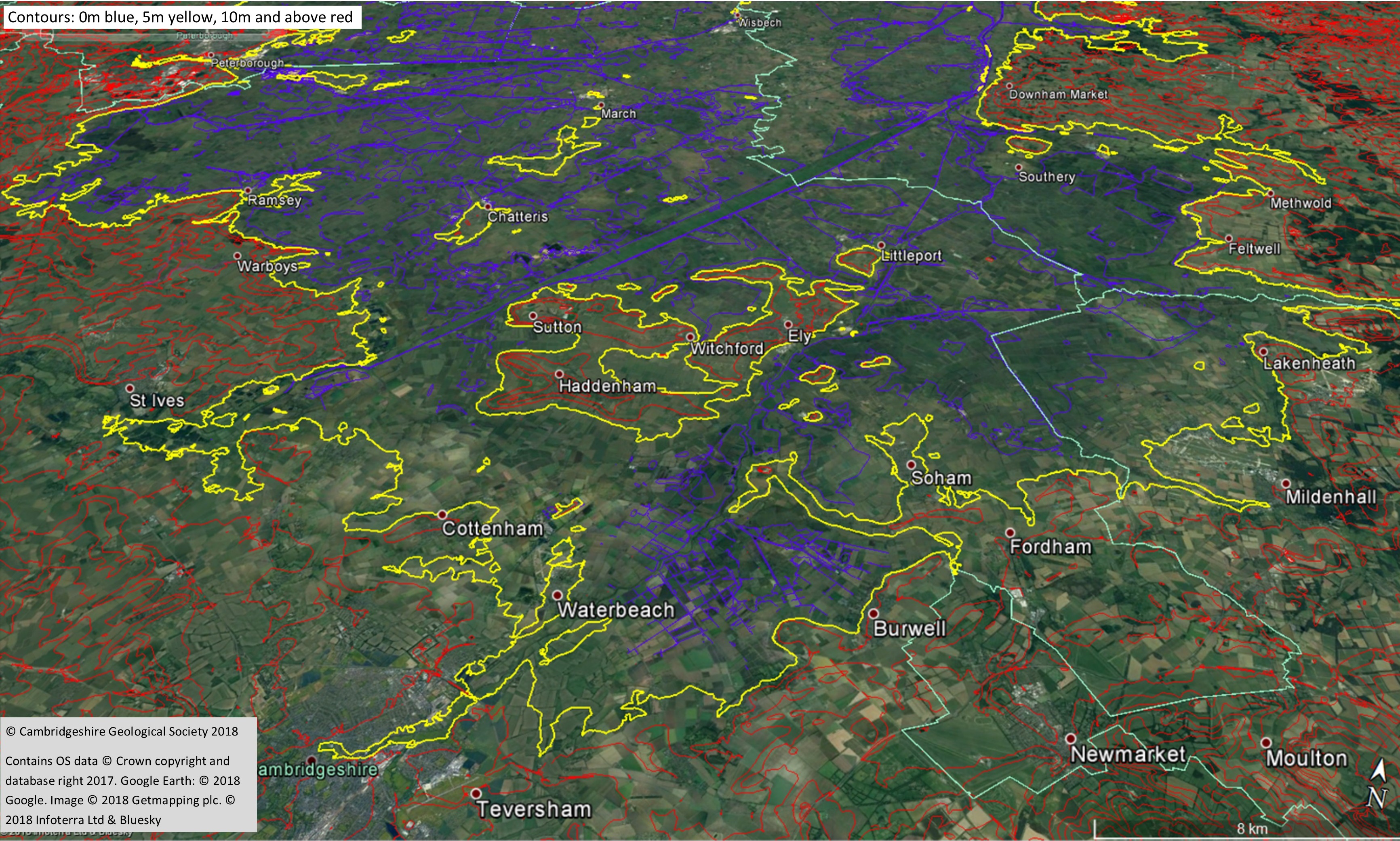

Complex landscape changes during the ‘Ice Age’ have formed the fenland basin itself as well as the fen islands that are now so iconic, and these changes have also resulted in dynamic river systems that have left their traces in the many patches of river terrace gravels that have given its human population important refuges over thousands of years and, more recently, have provided material for a significant mineral industry.

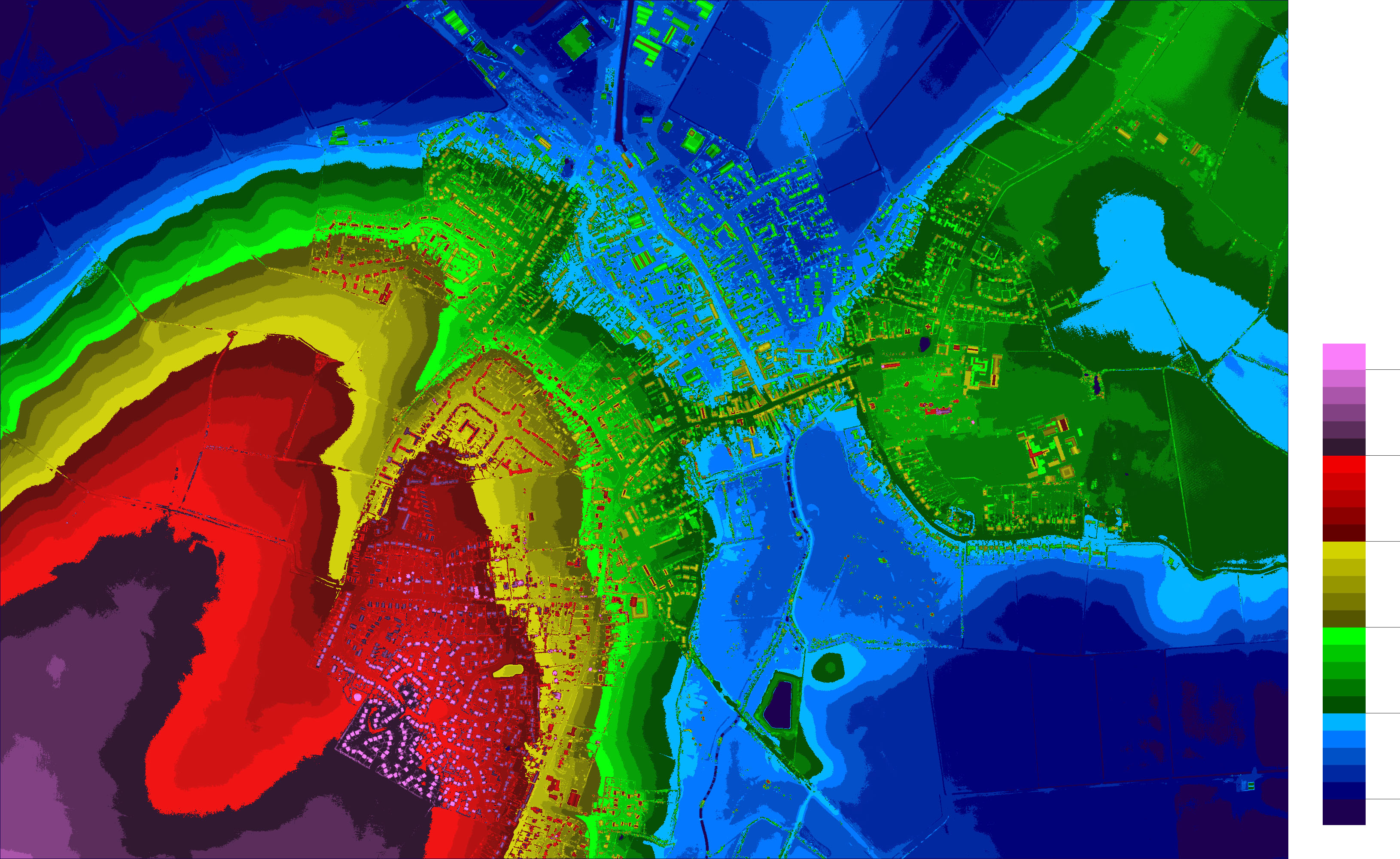

In the several thousand years since the ‘Ice Age’, the now familiar fenland landscape has evolved but it is a far more complex story than most people imagine. Not only do the different areas of the fenland have their own landscape history, there are often significant differences from one field to another – mostly the result of the ever-changing (until relatively recently) patterns of drainage– both natural and man-made. The chance to look down a few metres from the surface often shows a changing pattern of material that reflects the changing environment and climate. As well as the infamous peat, there are deposits of marine silts and clays – a legacy from the brackish conditions of saltmarshes – and material from ancient channels whose courses can sometimes still be seen on the surface in aerial photos, as well as marls from lake beds long disappeared, and sands and gravels and alluvial material from recent rivers. The small remnants of alkaline fen that still exist and the even smaller patches of the remains of acidic bog provide glimpses into ecologically rich and varied landscapes that gradually formed the extensive mosaic of peatland deposits that have not only given us so much information on changes in past vegetation and climates but also preserved valuable artefacts from our cultural history.

The importance of the geology of the Fens, particularly as a record of past climates and environments, is shown by the designation of the area of Holme Fen and Whittlesea Mere being designated a Local Geological Site. Three more sites are also now designated as Local geological Sites for their fenland deposits (Holocene geology). These are Sedge Fen and Reach Lode Bridge at Wicken Fen and The Hythe at Reach.

More information on the landscape and geology of the Fens can be found on our Fen Edge Trail website.